- Home

- Wendy Percival

Blood-Tied Page 3

Blood-Tied Read online

Page 3

‘What’s the matter? What have you seen?’ Gemma looked down at the certificate, her eyes rapidly scanning it. ‘Tell me. What should I be seeing?’

There was no way Esme could prevent Gemma from seeing what she herself had just noticed. Sooner or later she’d study it and come to the same conclusion.

Esme laid a finger on the section where the date of the birth was recorded. She hadn’t immediately noticed it, being drawn instead to the name.

Gemma read it out loud. ‘Twenty-eighth of March 1956.’ She looked at Esme. ‘That’s Mum’s birthday.’ Her brow puckered. ‘I don’t get it. Who does this belong to?’

Esme hesitated. She wasn’t jumping to conclusions was she? What else could it be? And if Gemma had any idea what Esme was talking about she wouldn’t be looking as confused as she was. So she hadn’t known either.

Esme looked around. ‘Where’s the envelope this came out of?’

‘Esme, for goodness sake! Tell me. Whose birth certificate is this?’ Gemma thrust the document at Esme.

Esme didn’t answer. She snatched up the discarded brown envelope and pulled out a second piece of paper. She scanned it and then slumped against the back of the chair. The image of the two people in Elizabeth’s locket flashed into her mind. It had to be.

Gemma was staring at her. ‘What have you found?’ she said, her voice barely above a whisper.

Esme looked up and held out the document in her hand. ‘It’s an adoption certificate. Your mum was born Rosie Roberts. She was adopted before I was born and renamed Elizabeth.’

The implications of what she’d just said hit her like a door being slammed in her face. Elizabeth wasn’t her real sister.

3

From Esme’s favourite spot on The Long Mynd in the Shropshire hills, it was often possible to see several counties. But today the weather was hazy, which aptly reflected her state of mind. She stood, hands deep in the pockets of her duffel coat, and stared out across the expanse of the undulating landscape around her.

When she had read Elizabeth’s birth certificate she had felt suddenly stupid. She had started dabbling in her family history when she first moved back to Shropshire. Her friend Lucy suggested it as a way of rekindling Esme’s talent for investigation which she had rejected following the untimely death of her husband Tim, an investigative journalist. Pursuing it again had proved cathartic. Slowly and tentatively she re-engaged with the world of research. At least, on her own terms.

How cruelly ironic that, while researching her genealogy, she had been completely unaware of the details of her immediate family. It made a mockery of being able to trace your ancestors back to the seventeenth century, when you were ignorant of the fact that your own sister wasn’t part of your bloodline. But then who, when starting out, began by checking the legitimacy of their own siblings? Not unless they had cause to suspect something, which she never had. Should she have? The feeling of foolishness had slowly over the past few hours given way to a sense of betrayal. Why had she never been told?

Gemma’s first reaction had been one of disbelief until Esme explained about the photographs in the locket. Perhaps she herself had looked inside and been similarly puzzled because she fell silent. When Esme asked the question most pressing in her mind: why neither of them knew of Elizabeth’s adoption, Gemma had shrugged and said something about Elizabeth having her reasons. But despite her apparent casual manner she looked to Esme like a person in shock.

After they had returned from Elizabeth’s, Esme had felt a compelling urge to visit her parents’ grave. In the last couple of hours of daylight she drove out to the village where they had lived. She stood by their headstone in the diminishing light, and the chill of an easterly wind, desperate for some sense of understanding as to why they had kept Elizabeth’s past a secret from her. The questions whipped around in her head, mimicking the wind in her hair. Were they protecting Elizabeth?

Had Elizabeth always known or had she found out later? There was no way of establishing that until Elizabeth woke up and answered the question. The date of the certificate copy was 1977, the year after the act was passed allowing adopted children the right to see their original birth certificate, and so learn the names of their parents. Elizabeth would have been twenty-one. Was she told then because she had reached a significant age? Or had she grown up with the knowledge that she was adopted and had taken the first opportunity to take up her right to know the details as soon as the act became law?

A couple of hikers came into view. Esme nodded ‘Good morning’ to them as they passed by. She had hoped that the walk would help her to put the situation into perspective but she had to admit that her usual source of solace wasn’t giving any comfort. She decided to retrace her steps and return home.

As she walked she thought back to her childhood. Had anything ever been said, or any event happened which indicated the true relationship? Nothing came to mind. Unless the difference between the two of them was a clue. Elizabeth had always been such an exacting child, whereas Esme was happy-go-lucky in her approach to life. Elizabeth was very particular and everything had to be just so. She hated being called anything but Elizabeth, never Liz, or worse, Lizzie. Esme used to tease her by calling her ‘Lizzie Dripping’, from a children’s television programme of the time. Elizabeth loathed it. She tried to get her own back by calling Esme by her full name, ‘Esmerelda’, but Esme would remark that it sounded like a princess’s name. She smiled at the memory.

Was there something in Elizabeth’s development which was influenced by her knowledge that she had been adopted? Was her need for everything to be ordered and precise part of her security? Esme tried to understand her parents’ role. These days it was assumed that adopting parents were honest with their children about their parentage, but Elizabeth would have been adopted in the 1950s. Attitudes were different then. Esme guessed they had kept it from Elizabeth because if she had been told then surely they would have had to tell Esme. But Elizabeth had known since 1977 at least, in order for her to obtain a copy of her birth certificate. Why hadn’t she told Esme? Because she was at university and away from the family home? Was that it? Surely not a good enough excuse. But after that, Esme had hardly been home, working away in London with Tim on the Mail and then going abroad. And later, when Esme was dealing with the trauma of Tim’s death and her own disfigurement, Elizabeth might easily conclude that it was not the time to make such a confession to her younger sister.

But Esme was determined not to give Elizabeth an excuse. She should have told her, whatever the circumstances. Nothing so important should be allowed to stay secret. What had she thought Esme would say? Had she feared rejection?

By the time Esme had stomped her way back to her car she knew what she wanted to do. She fumbled in her pocket for her keys and slid the key into the lock. She had, after all, gained some clarity as a result of her visit. She knew that she would not be able to sit back and wait until Elizabeth was able to explain everything. She wanted to find out the truth for herself.

She stopped abruptly, a particular question reverberating in her head – the attack, the argument in the park, the suspicious visitor at the house. Were these connected to Elizabeth’s hidden past? And if so, what exactly had Elizabeth got to hide?

4

Gemma was at Elizabeth’s bedside when Esme arrived at the hospital later. Esme stood at the bottom of the bed and studied Elizabeth’s face. Were the bruises fading yet? Were there signs that she was coming round? The machines clicked and hummed but Elizabeth lay still, the only movement the barely perceptible rise and fall of her breathing.

Gemma stirred and stretched her arms above her head. She stood up. ‘I could do with a cup of coffee.’

‘Shall we go to the canteen?’ suggested Esme. She draped her coat over the chair that Gemma had vacated. ‘I’ll sit with her for a while afterwards, if you like. You have a break.’

They

took the lift to the basement canteen and seated themselves at a table in the corner.

‘How are you?’ asked Esme. ‘Are you getting enough sleep?’

Gemma shrugged. ‘So-so. Helen’s on nights at the moment so she kicks me out when she comes on duty and sends me home to bed.’

‘What about food? Are you eating?’

Gemma gave a wry grin. ‘What’s this? Aunty Esme fussing?’

‘Your mum wouldn’t thank me for allowing you to wither away while she’s in the land of the sleeping beauties, now would she?’

‘No, perhaps not. But I’m perfectly capable of looking after myself, you know.’

Esme felt the comment was an unnecessary rebuff but perhaps she was being oversensitive, especially under the circumstances. If Gemma didn’t see that their relationship had changed, why should Esme? She pushed the thought away. ‘There’s nothing wrong with being pampered once in a while. Why not come round for something to eat later?’

Gemma wrapped her hands round her coffee mug. ‘It’s tempting,’ she admitted. ‘I’m going over to Mum’s to pick up her post again tonight. Shall I drop in afterwards?’

‘You do that.’

They sipped their drinks in silence.

Esme was aware that someone was walking towards their table. She glanced up and recognised one of the policemen they’d seen on that first day.

She spoke to him as he approached. ‘DS Morris, isn’t it?’

He grinned. ‘That’s right. Sorry to spring upon you, ladies, but the nurse upstairs said you were here.’ He gestured to a spare seat. ‘May I?’

Esme nodded. The sergeant pulled out the chair and sat down. He delved into his pocket and brought out a picture of a man’s face. He laid it on the table and slid it across to them.

‘Our witness came up with this likeness.’

‘Esme said you had a witness.’ Gemma drew the paper towards her. ‘So this is Mum’s attacker?’

‘We don’t know that,’ cautioned the sergeant. ‘The witness only saw the argument.’

‘What argument?’ Gemma looked up at the sergeant and followed his gaze as he glanced across to Esme. ‘Do you know something I don’t?’ she said.

Esme cleared her throat. ‘The inspector mentioned an argument that first day. I forgot to tell you.’

‘How could you forget something like that?’ said Gemma accusingly.

‘I was rather preoccupied with how your mum was,’ Esme said in her defence. She cursed herself for not dealing with it before. She hoped Gemma wouldn’t say any more on the subject in front of the sergeant. The police didn’t need to conclude they were dealing with a dysfunctional family or they might start looking into Elizabeth’s background. Gemma wouldn’t like that.

‘Anyway,’ interrupted Sergeant Morris, much to Esme’s relief. ‘If we could just get back to this suspect.’ He tapped his finger on the paper. ‘Do you know this person, by any chance?’

They leant over and studied the picture on the table. The man was probably about thirty, gaunt face, with wispy collar-length hair.

Gemma shook her head. ‘No idea.’

Esme continued to stare at the picture. ‘He doesn’t ring any bells with me. And they were definitely arguing?’

‘The witness was some distance away so she didn’t hear what was said, just that it was clear they were quarrelling. She said it looked pretty heated, as we mentioned to Mrs Quentin.’

Gemma threw a sharp look at Esme, but took out her antagonism on the sergeant. She shoved the picture back across the table.

‘This is ridiculous. The woman probably went home, watched her favourite soap and a game show before she realised the significance of the man she’d seen. By the time she’d reported him to the police any number of faces could have cluttered up her memory banks. If you match his face to the cast list of Emmerdale, you’ll find he’s one of the actors.’

The sergeant gave a sardonic smile, but made no comment. Instead he changed direction. ‘Does either of you know the name Leonard Nicholson?’

They both shook their heads. ‘Who’s he?’ asked Esme.

‘Someone we’d like to talk to.’

‘What’s the connection?’

‘We don’t know there is one. One of my colleagues said he thought there was a likeness but…’ he shrugged his shoulders. ‘I don’t think so, myself. Not his territory.’

‘As in the place, or mugging?’

‘Both. So did you find anything on the calendar?’

Esme opened her mouth to answer but Gemma cut her off. ‘No. Completely blank.’

The sergeant stood up. ‘Ah well. If you do come up with anything, you know where we are. I’ll leave you in peace.’ He nodded to them and left.

When he’d gone Esme looked hard at Gemma. ‘Why didn’t you mention about the W.H. on the calendar?’

‘What’s the use? We don’t know what it means, why should they? More to the point, why didn’t you tell me about the argument?’ She sounded as though she was trying to control her temper.

Esme cradled her mug. ‘Sorry about that. To be honest, at the time I took what they said with a pinch of salt.’

‘Why?’

‘A bit like you with the photofit, or whatever they call them. Someone’s over active imagination.’

Gemma sighed but said nothing.

‘So what do you make of it?’ prompted Esme.

Gemma shrugged. ‘I don’t know what to think.’

‘Or want to?’

Gemma looked up with narrowed eyes. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

Esme tried to make her voice sound casual. She didn’t want her question to sound like an accusation. She simply wanted an honest answer. ‘Don’t you want to find out what’s going on?’

‘There’s nothing “going on”, as you put it.’ Gemma’s tone was indignant. ‘Poor Mum was at the wrong place at the wrong time and some junky got lucky.’

‘But aren’t you interested in why she was there at all? You’ve got to admit it’s odd, even if we both think the argument idea is unlikely. And now with finding out what we did…’

Gemma stood up and pushed back her chair, the legs scraping noisily on the tiles, drowning out the end of Esme’s sentence. ‘I’m more interested in Mum getting better,’ Gemma said haughtily. ‘As you should be.’

And she turned and marched away.

*

Chopping onions allowed Esme’s emotional tears to mingle with the onion induced ones and relieve some of her inner turmoil. Already emotionally confused by the revelation of Elizabeth’s secret, there was now Gemma’s state of denial to deal with and her determination to remain as blinkered as possible. How was that going to square with Esme’s own decision to delve more deeply?

She sighed, sensing there were turbulent times ahead. She might be prepared for them but she didn’t expect to relish them. It was a relief to let the tears run down her face and not feel the need to curb them.

She had no idea whether Gemma would turn up. By the time she had followed her back to the ward after their exchange in the canteen, Gemma had already left. The only clue Esme had that she wasn’t completely excommunicated was that Gemma had left a message with the duty nurse to say she’d gone to Elizabeth’s house. Esme took that to mean their arrangement still stood.

The doorknocker sounded. She wiped her face with the back of her wrists and went to answer the door.

‘Onions,’ she said to Gemma’s alarmed face. She stepped back to allow Gemma in.

Gemma took off her coat and dropped it over the arm of the sofa. ‘Brenda’s going to send on the post,’ she said. ‘Saves me going over.’

‘That makes sense. Come on through.’ Esme headed for the kitchen, relieved to see that Gemma had decided that their earlier disagreement was a thing of the past. Unless this was h

er way of avoiding the difficult issues, by pretending they hadn’t happened. Time would tell.

Esme grabbed a couple of wineglasses and a bottle of Merlot from the dresser.

‘Fancy a glass?’

‘Yes please.’ Gemma plonked herself down at the kitchen table and dropped the heap of envelopes next to her. Esme handed her a glass of wine.

‘Cheers. Here’s to Mum’s recovery,’ toasted Gemma.

‘Ditto to that.’ Esme sipped her wine and then turned back to the onions. ‘I usually chop these things outside, but it’s a bit wet for that.’

Gemma glanced out of the window. It had been a day of heavy showers and another was rattling against the window panel of the stable door.

‘Outside?’

‘Yes. You don’t suffer the effects.’

‘I suppose not. I’ve never thought about it. You’re a mine of information, Esme, d’you know that?’

Esme gave a weak smile and slid the onions into the pan. They hissed as they hit the hot oil. Whatever mine of information she usually enjoyed seemed to have deserted her for the moment. If there was a mine analogy, it was that she was fumbling around in a dark place like a nineteenth-century collier with only a single candle to light the way.

Esme added the remaining ingredients, turned down the heat and left the pan to simmer. She turned to Gemma who was idly sifting through the post she had collected from Elizabeth’s house. Esme picked up her wine and went to join her at the table. She took a sip and studied Gemma over the top of her glass. She had stopped flicking through the pile and was frowning at one letter.

‘What have you got?’ asked Esme.

‘I don’t know. It’s the way this is addressed.’

‘How d’you mean?’

‘Well, you know what a stickler Mum is for convention and her obsession with being Mrs P Holland? I could never see what the problem was.’

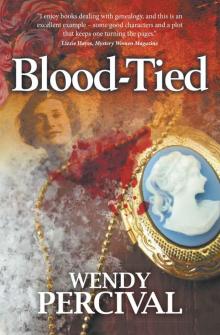

Blood-Tied

Blood-Tied